Before anything else, I want to share a personal story about The Music Machine in October of 2016 I began to play through this wonderfully atmospheric first-person horror game for the sake of writing an article about it. Unfortunately, I accidentally overwrote my save data and lost some progress, but this isn’t a particularly long game so that wasn’t really much of an issue. Except, then my entire hard drive died and with it went my save file until I found a replacement. Then my computer died, taking my third save with it. Once everything was back in order the Halloween season was long over and plans to write about The Music Machine fell through the cracks.

With Halloween once again on the horizon, this week seems like the perfect time to at last delve into this story about a girl, the ghost possessing her, and the mysteries surrounding a very creepy and exceedingly orange island.

the setting and your role as the player are unusual this time around to say the least. Specifically, you take on the role of a vengeful ghost named Quintin, who has in turn been possessing a 13 year old girl named Haley for three months prior to the start of the game. Though Quintin has control, Haley is still fully capable of speech and often comments on sensory details that Quintin doesn’t notice as a ghost.

As for the setting of The Music Machine, the game takes place on an island with an abandoned campground where several gruesome murders took place. As to why our unusual duo have come to this island, Quintin wants to find the murderer in order to give Haley a death he’d be satisfied with while Haley doesn’t believe Quintin is serious about wanting revenge and generally maintains a more upbeat attitude.

Before venturing beyond the basic setup for this game, I’m going to give an important disclaimer. The Music Machine revolves almost entirely around exploration and discovery, but it’s also on the shorter side, coming in at about two hours or less even if you actively explore your surroundings. As such, I would strongly recommend putting this article aside and playing it for yourself if at any point it sounds interesting enough to warrant a potential purchase. I’m going to be keeping this article on the vague side of things, but it’s impossible to discuss The Music Machine without at least alluding to some of its bigger surprises. This disclaimer is especially important because, after all, this is a horror game and even hinting at the nature of the horror elements spoils the experience somewhat. With that warning in mind, let us continue on our way!

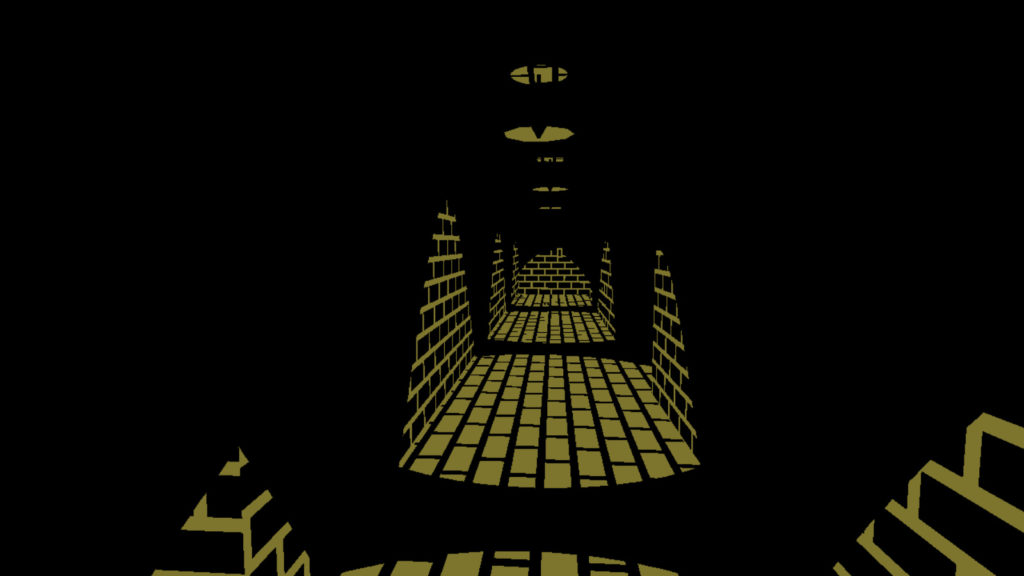

The first thing you’re bound to notice is just how orange everything is. The water’s orange, the sky’s orange, the ground is orange, even the trees and buildings are all orange. What’s more, they’re all the exact same shame of orange contrasted with pure black shadows and outlines. The color changes when you go inside cabins and other locations, but you never have more than black and one other color at a time. It’s a striking stylistic choice and one which fits the nature of this game perfectly. Boundaries are often initially unclear and common objects can appear strange and menacing while the unusual can appear relatively normal until you take a closer look.

The Music Machine constantly plays with perception, both your own perception as the player and the concept itself. I’m tempted to call this game cosmic or supernatural horror, yet the former label is heavily tied to Lovecraftian themes which aren’t strongly present here while the latter generally implies the inclusion of jump scares and/or ghosts, neither of which are present here aside from Quintin. So, let’s say this game belongs to an entirely different subgenre instead, let’s call it “perceptual horror”. The way perception twists and turns about in this game can be observed even in your own character. Quintin’s technically the one in control, but you’re seeing the world in first-person through Haley’s eyes, so are you really playing as Quintin or Haley or both?

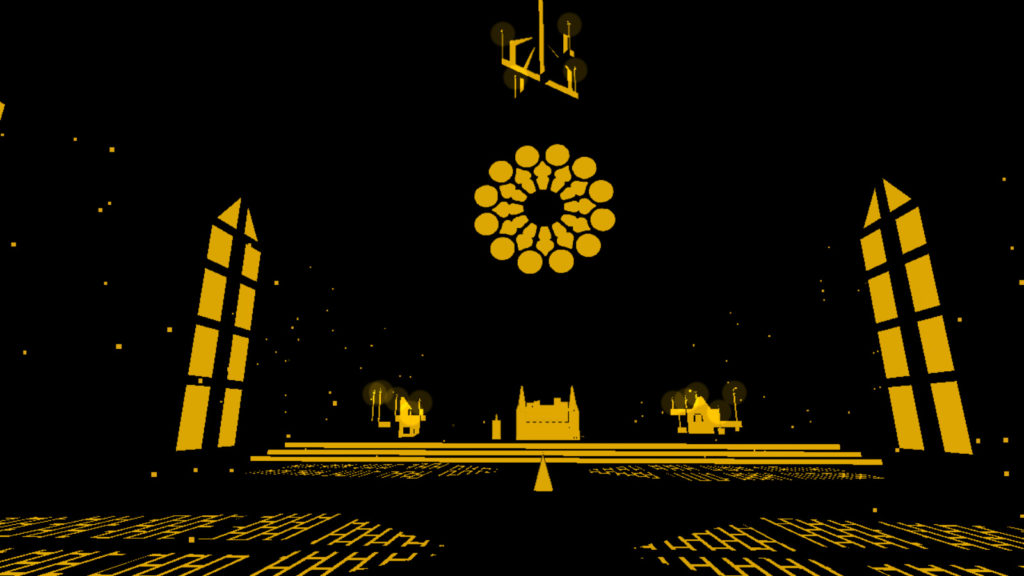

When it comes to perceptual horror, one of the biggest examples of this concept, both literally and figuratively, is a particular building you can come across on the island. Though the island has its share of abandoned cabins and crumbling ruins of other buildings, there is one building which stands out – a massive church. At first, the church may look perfectly ordinary aside from its presence in the midst of a campground. However, the giant cross on the building’s roof is upside-down, a detail both Haley and Quintin confirm if you examine it. Upside-down crossing are hardly out of the ordinary in the realm of horror, but in this case I suspect that this cross mostly exists to lull players into a false sense of security concerning what ‘type’ of horror they can expect from this game. For you see, the true surprise lies not in the reversed cross, but in the seemingly ordinary doorway. Upon trying to open the door to the church it is revealed that there is, in fact, no door at all and it is merely the shape of a door drawn in the wall.

the doorway reveal is a brilliant twist which takes full advantage of both the art style and the player’s own expectations, but it also serves to highlight why I hesitate to place this game into the cosmic horror genre. A common theme in cosmic horror is the vast and unknowable nature of the monsters. Within cosmic horror, the protagonists rarely battle an antagonist so much as they strive to simply survive against the embodiment of the smallest sliver of a vast force they cannot hope to ever comprehend.

In The Music Machine it soon becomes clear that something inhuman is involved in the events on the island, but it’s the opposite of the typical Lovecraftian take on cosmic horror. Rather than the protagonists being up against something they cannot comprehend, they are up against something which cannot comprehend humanity. The church doesn’t have an upside-down cross because it’s evil, it has such a thing because it was built by something which perceives a church as a giant box with a cross on it. There is that common cosmic horror sense of ‘wrongness’ here, but this time around it comes from seeing basic, common objects like a door being fundamentally misunderstood by their designer. What is a music machine to a being which cannot understand a door?

Most of the character developer and background details occur via flavor text. In that regard, how much you get out of this game depends in large part upon how much you’re willing to put in. Quintin and Haley often have conversations after you reach new areas and after solving some very simple puzzles, but these conversations largely serve to give you a general idea of the plot and these characters. As such, examining every object you can, even seemingly inconsequential ones, can reveal quite a bit. Quintin and Haley frequently talk to each other when you examine things, which can reveal new facets to the nature of their previous and current relationship. Likewise, in a setting where increasingly few things are exactly what they seem to be, the flavor text from examining objects reveals all sorts of unsettling details, such as what looks to be a pile of hay actually being a pile of needles. Notes from previous residents of the island and more ordinary details, such as which beds have or have not been slept in recently, also help to expand upon the setting.

As much as I enjoy The Music Machine, it does have a few places where it stumbles. First, the exploration in this game is oddly top-heavy. The initial island area is respectably large and has a good number of completely optional cabins and ruined buildings to check out, each of which has various objects to examine for insight. the first half of the game also has what I will refer to as the “red area” which likewise is rather open and brimming with things to discover and inspect. However, areas you reach in the latter half of the game tend to be either fairly small and confining or fairly large, but with very few objects you can choose to examine.

Another, more minor, issue is that flavor text never seems to change. Early on this doesn’t matter much and there is quite a lot of flavor text in this game regardless. Even so, the static nature of the flavor text does stand out a bit when you need to do some brief backtracking in the second half. Going through old areas and getting the exact same dialogue as before upon examining objects despite some fairly significant revelations later on breaks the sense of immersion somewhat. As a side note, there are multiple times in the initial conversation between Quintin and Haley where ‘loneliness’ is spelled as ‘lonliness’, which does give the game a bit of a rocky first impression.

Far and away the biggest issue in The Music Machine occurs in what I’ll be calling “the room”. Generally, this game is good at parceling out small fragments of its story and revelations often end up raising new questions. It doesn’t quite stick to the golden rule of “show, don’t tell”, but that’s largely because it loves to play with your sense of perception by showing you what you thing is one thing only to have it be revealed through dialogue as something else completely. However, all of this changes in the room. Once you enter the room, a very long conversation occurs in which the full nature of the antagonist is not only revealed, but you even get to learn about their backstory alongside a whole lot of other information about the setting. The curtain isn’t so much pulled aside as it is torn down and tossed in the trash and only a few precious threads of mystery remain by the conversation’s end. Mystery and horror go hand in hand and games like Close Your Eyes prove how effective and exciting it can be to leave some interpretation up to the player so I am rather baffled by the decision to place such an unnecessary glob of exposition in the middle of a game which is otherwise incredibly good at parceling out information.

Even with its issues, The Music Machine is one of the most fascinating horror games I have ever played. It takes full advantage of its minimalistic coloration to seamlessly blend the utterly alien in with the perfectly ordinary, forcing players to doubt their own perception of anything within the game’s world. The concrete facts surrounding the previous murders on the island always hover in the back of your mind to help keep you on edge; there is something unknown on this island and it has proven itself to be dangerous. Your own role as the player is also a rather disturbing one if, unlike Haley, you believe Quintin to be sincere in his desire for revenge because that would mean every action you take is for the sole purpose of delivering a victim to a murderer. The Music Machine may be on the short side, but it leaves an unforgettable impression.