Epikos is, rather unsurprisingly, the Greek word for ‘epic’ and Epikos is aptly named indeed. Focusing more upon its lore than its plot, this RPG by Hummingbee Games is steeped in the traditional ways of the old poetic tales with deeds of valor, larger-than-life heroes and villains, grand myths, forgotten legends, and dark prophecies. This isn’t to say that Epikos is completely without a sense of humor or that it ignores more modern literary techniques when it comes to character development, but a person may very well decide to brush up on Beowulf by the time they’re done.

A large part of what sets Epikos apart from most other games is its refusal to focus solely upon the exploits of a single protagonist, though there are two in particular who are central to the plot. Players initially take on the role of Zenton, an aged yet inhumanly strong knight with unflinching loyalty to the king of Evermarch. Everything about Zenton from his achievements to his personality (to say nothing of his ability to kill nearly any enemy in a single hit in combat) makes him seem like a legendary hero and his initial presence sets the tone perfectly – this is a story with a grand scope filled with miracles and tragedies and it begins on the closing chapter of Zenton’s own saga. Zenton may set the tone, but this is not solely his story and he eventually becomes part of a revolving cast of characters whose paths cross and uncross over the course of the game.

Standing in stark contrast to Zenton is Greenwood, a relatively young member of an order of rangers and by far the closest this game gets to having an ‘everyman hero’ amongst the playable characters. If Epikos serves as the closing chapter on Zenton’s story, then it is the opening chapter of Greenwood’s. Players first gain control of Greenwood at roughly the two hour mark after certain events force him to venture far across the world for the first time. Possessing not even a third of Zenton’s HP and relying on traps and ranged attacks as opposed to charging into the fray, Greenwood differs as much from Zenton as much in combat as he does in characterization. Greenwood is certainly not a bystander nor is he caught up in events against his will, but he is more naïve and inexperience than many other members of the cast and spends most of his journey following the directions of others. The remaining playable characters all get their own moments to shine, but their roles are largely tangential to the stories of Zenton and Greenwood.

Lore is far and away the biggest part of Epikos and how much mileage a player gets out of this game will vary wildly depending on how deeply they care to dig into these optional pieces of information. Several ancient tablets are scattered throughout the game, some of which can be purchased from shops while others need to be found, and these can be taken to bards to have them recite pieces of lore, many of which shine light upon several of the game’s events and characters. However, lore really comes into play with the dialogue system. Anyone familiar with older computer RPG’s will likely recognize the keyword system at play here. Players have no control over the flow of dialogue in cutscenes, but conversations can be started with nearly any one of the dozens of NPC’s in the game through the use of a single word or short strings of words. By default players are given three basic words to try out when interacting with NPC’s, ‘name’ and ‘job’ usually results in the NPC stating their name and occupation or whatever they are currently doing and ‘look’ repeats the initial description given of the NPC, but players are free to type in whichever words they desire. On a few occasions it is necessary to use the dialogue system to progress the game, but these instances are rare and easily resolved.

Those looking for tangible rewards from the dialogue system are bound to be disappointed; there is no way to affect an NPC’s mood or opinion and, to the best of my knowledge, conversations never start sidequests, grant items, or lead to any other form of optional content beyond the knowledge gained from the conversation in and of itself. That said, many NPC’s have multiple conversation paths which can often be started by asking them about their profession, another character, or vague topics, such as ‘history’, and a great deal of information concerning each town and its inhabitants as well as the mythology of the world as a whole can be gathered through these conversations. This process of piecing together information works particularly well for the setting because the world of Epikos feels like it is one on the verge of entering a new era; references are made throughout the storyline to dead or dormant mythological figures and factions and a handful of strange spirits and suspicious characters are scattered throughout the game, but the main narrative rarely goes out of its way to explain their significance. They may be vastly different games, but playing through Epikos without diving into the conversation mechanics would be like playing Dark Souls without reading item descriptions; you can certainly decide to ignore this part of the game, but doing so would mean missing out on understanding a great deal about the characters encountered and the events which occur over the course of the game.

Epikos has what it refers to as ‘beautiful 16 color graphics’ and, for the most part, this aesthetic works for it. There is a surprisingly large amount of variety to the spritework for such a limited color palette, both for character designs and environmental objects, and the game looks quite nice overall. A sight system also exists where players can only see in a 3×3 tile grid directly surrounding their character when in dense surroundings, such as on forest tiles, and shadows fill in tiles in relation to the player’s line of sight. If there is one area where I take some issue with the graphics, it’s with chairs. The player’s character will automatically sit in a chair when they move onto the same tile as one, but this turns them into a generic grey stick figure and makes it somewhat hard to take any cutscene seriously if a character is sitting down. This is mostly a minor complaint as there are quite a few different types of chairs in the game and the tile-based nature of the spritework combined with the fact that nearly any party member can be set as the leader means that a great number of additional sprites would have been needed just to show each character sitting in every possible type of chair, but I do think the game would have benefited from the inclusion of a handful of custom sprites to cover cutscenes where specific characters sit in specific chairs. As to the music, the tracks themselves are made well and fit the parts they are made for, but there are also only about a dozen songs in the entire game and, for a game which draws so much influence from the melodic prose of bardic storytelling, the low track count is definitely disappointing.

The retro aesthetics aren’t entirely for show as the gameplay takes after the RPG’s of a bygone era, though not without a few modern twists. Movement both in the world and in combat is entirely based on a tile grid and, though characters animate, they always face in a single direction. The actual act of movement is tied to the arrow keys, but the actual act of interaction is not tied to a single button and follows a more archaic model where players must press ‘E’ to enter towns and other areas, ‘T’ to start a conversation with an NPC, ‘S’ to create and name a save file, ‘I’ to open the inventory, and so on. This outdated mode of interaction would be annoying, but the nature of the conversation system already demands a keyboard and the usage of such specific key bindings doesn’t get out of control; other than the use of ‘Y’ and ‘N’ to confirm or cancel purchases from shops (and the use of ‘L’ to load if necessary), the key bindings I mentioned above are the only ones used outside of combat for all purposes other than for a handful of specific, highly contextual situations and a reference can even be brought up from the main menu. These interactions could result in some frustration from any who go into Epikos with no experience with such systems, but they are refined and streamlined enough that they I can only view them as a deliberate and ultimately harmless tribute to a past age in gaming.

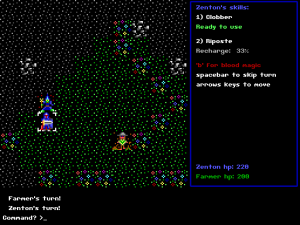

The combat system also takes a few notes from the past. Encounters are visible on the map and touching an enemy results in being transported to a rectangular grid where the player’s party appears near the bottom and the enemies start by the top. Every party member gets a turn before the enemies can act and that turn can consist of moving a single tile in any cardinal direction, using an ability, or simply passing. The majority of party members are extremely fragile and will usually die in two or three hits from just about any enemy, or even in one hit from some of the stronger creatures in the game, so avoiding damage by placing barriers or by positioning party members so that their attacks can intercept incoming enemies becomes very important. There are no combat items, no levels, and not even equipment exists so learning each character’s strengths and weaknesses is necessary as fragile characters will remain so for the entire game. Every character has somewhere between two to four skills, default ‘normal attacks’ do not exist, and most skills go into cooldown for a round or two before they can be used again. Characters almost never gain new skills or upgrade existing ones, but the exact composition of the party is changed up frequently enough that you never get stuck using the same tactics for any particularly large amount of time.

Blood magic and the way each character functions add some interesting twists on the combat system. Every character in the game can cast blood magic, but making use of this magic is not as simple as using a skill. Spells for blood magic can be found throughout the game with the general rule being that the shop in each town offers a unique spell and any spell can be cast by every character once it is purchased. There is no cooldown on blood magic, but it does cost blood crystals. Jars are scattered throughout the game and each can hold one blood crystal; blood crystals themselves are randomly dropped by enemies upon killing them in combat and touching them instantly restores 50 HP to the entire party (many characters only have 200 HP so this is actually a substantial amount) and puts the crystal in a jar if there is room for it. Spells for blood magic cover the entire spectrum from damaging magic bolts to party-wide heals and there’s even a revival spell and a shield; virtually every blood magic spell is useful and having a few blood crystals on hand can often turn the tide. As to the characters themselves, each has a distinct form of attacking and defending via their skills. For example, Annah can create magic shields and can place blocks of magical motes on the field, which do nothing on their own, but damage any enemy they are touching when she ‘channels’ them, after which she can send out a single, highly-damaging bolt of energy. Meanwhile, Farmer (yes, that’s his name) can dance to gradually spread grass or rock tiles and then use his ‘Earth Maw’ ability to remove these tiles and deal high damage to every enemy standing on one of these tiles.

As much as I enjoyed my time with Epikos, it does have some significant flaws. A button can be held down to rapidly run in a direction, but doing so outside of towns and other safe areas is often hazardous as entering an encounter while running almost inevitably leads to accidentally wasting a few turns moving the entire party in whichever direction you were running in; the addition of a mandatory button press to start combat after entering an encounter would have easily solved this. A more important, overarching issue is the fact that Epikos simply feels overly sparse in several ways. Environmental hazards or barriers do not exist in combat outside of ones created by the party or enemies and, though terrain may exist to slow you down or limit your sight outside of combat, terrain tiles have no impact in combat; different layouts for battle arenas or terrain effects would have added a great deal of depth to the combat and it is a shame that neither exists here. There are several mandatory fights across the game, but these generally aren’t much harder than other encounters and outright boss fights are so rare that I could count them on a single hand. The overall lack of particularly dangerous fights against imposing foes undercuts the epic tone and scale the game strives to emulate. This sparseness also extends to outside of combat as the game itself is on the short side, roughly eight to ten hours though this estimate can vary based on how much time is spent in conversations, and can easily be finished in a day or two. As much as I like how lore is handled here and how well it is embedded into the world, I wish there was more to get out of the world than just lore; even when the game opens up more near the end the only optional content to find not related to one of the possible endings is, to the best of my knowledge, purely lore with no additional items, no hidden powers or characters, no secret dungeons, and no optional boss fights.

The quantity of content in a game is never as important as the quality of said content and I did consistently enjoy my time spent within the world of Epikos, but I have a difficult time recommended this game for its current asking price of $12 with how much it has to offer. On the other hand, I would definitely say that it is well worth somewhere in the $5-$7 range, or possibly slightly higher, so those interested in it should keep an eye on it and grab it the moment it goes on sale. Questionable price point aside, with so many RPG’s devoted to following the exploits of young stereotypes out to save generic fantasy settings from bland villains, Epikos comes as a much-needed breathe of fresh air and properly reminds us to honor and remember that which has been lost.

Hi this is Kingbee and I wrote Epikos!

Thanks for writing this article on my game. I’m glad you enjoyed your time, and you seem to really *get* what the game is about.

The game was really an experiment for me, since I wrote all the music, did all the programming, wrote all the lore, and made all of the art.

I agree with pretty much everything you wrote, and also of the game’s criticisms, which I would like to address.

More boss fights would have been great. The conversations are occasionally important, but given the potential of the conversation system, I believe that it could have been used *much* more effectively, mostly in the ways you mentioned. Hidden dungeons and characters would have been very good as well. The difficulty seems about middle-of-the-road, but I had intended to include a hard/easy mode, which I never ended up coding. And price point is a very confusing topic to me in general, as many people think I should charge more (~$20) as well as many think I should charge *less*.

This is a bit of an overlooked title I’d say, with only 450 or so people owning the game, but I think it fills a niche which is basically empty these days, or nearly so.

Anyway, thanks again for writing about Epikos.

–Kingbee

Thanks for the reply! Price points are definitely one of the hardest things to figure out when it comes to releasing a game. I’m not sure what itch.io’s policy is when it comes to adjusting prices, but if they’re lenient it could potentially help to try increasing or decreasing the price (or just putting it on sale) to see what happens. Game Jolt also recently started allowing commercial games; they’re still only slowly rolling out games from handpicked developers, but you might still be able to send in an application for later. Either way, I definitely enjoyed Epikos so I hope you find a way to get it noticed a bit more in the future!

Pingback: Nice, In-Depth Review of Epikos – Epikos