Chalk may be one of the older indie games developed by Joakim Sandberg, also known as Konjak and more well-known for Noitu Love 2 and the upcoming Iconoclasts, but it is far from unpolished. The title doesn’t just refer to the aesthetic as this bullet-free shmup challenges players to defeat their foes, overcome obstacles, and shield themselves from onslaughts of attacks all with a single piece of chalk.

The chalk-based gameplay of Chalk has a distinct resemblance to Kirby: Canvas Curse, which isn’t too surprising as the games released only about two years apart from each other, but the applicable uses of your limited line-drawing tool are much different here. The protagonist, Line, can freely move around the screen like in most shmups and players can freely choose between directly controlling Line with the WASD keys or moving Line’s spiky companion, Target, with the right mouse button and Line will follow along. As to the chalk itself, it can be used to draw lines by holding the left mouse button. A line of chalk does not have to be straight and it can freely overlap with itself, but it does have to be continuous; the current line of chalk will immediately vanish the moment the player starts to draw another line. Chalk lines fade away on their own after a few seconds even if a new line isn’t created and there is a line meter which rapidly drains while drawing to limit how long a single line can be, but this meter immediately refills after the player finishes drawing so there is no need to wait for it to recharge.

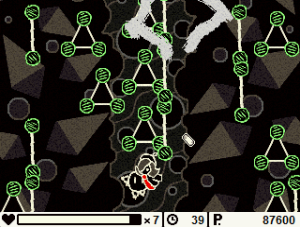

You might be wondering just what these chalk lines are even for if they aren’t required for movement. There are actually a few different uses and this is where colors come into play, but for the most part these lines are used for connecting dots. There are no walls in Chalk, but there are obstacles, primarily consisting of small, straight lines, rectangles in various sizes, triangles, and trapezoids. Each type of geometric obstacle has several green dots attached to it; lines have a dot on each end, rectangles range from having two to four dots on their corners, and all other shapes always have one dot on each corner. In order to destroy an obstacle, a line must be drawn which connects all of its green dots in any order and point bonuses are awarded for destroying multiple obstacles with a single line. As these obstacles often come from different parts of the screen or move along set paths, Chalk becomes a balancing act between waiting for the right moment to swiftly and accurately draw a line across the dots of as many obstacles as possible to obtain a high score while maneuvering Line out of harm’s way.

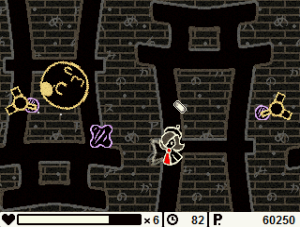

Obstacles and their green dots are only the beginning of Chalk’s colorful gameplay. Yellow enemies exist and range in form from generic ships to weird bouncing faces. Drawing on these enemies is not enough on its own to defeat them, but they can be stunned by mousing over them and holding down the button. To defeat yellow enemies, you must wait for them to launch a purple projectile, often in the form of a dot or a more powerful square blob. These attacks will be destroyed if they collide with a chalk line, but drawing a line which connects an enemy and an attack will both destroy the attack and damage the enemy. Even better, multiple projectiles and enemies can be connected with a single line, so connecting two projectiles and three enemies would deal two points of damage to all three enemies simultaneously. Obstacles give bonus points simply from destroying two or more of them with one line, but for enemies players must perform an ‘overkill’. An overkill occurs when an enemy takes more damage than its maximum health and this can require some strategy as each enemy only has one projectile out at a time. Thus, in order to get the maximum possible overkill bonus a player must deliberately reduce each enemy to a low amount of health without killing it and then chain together the attacks from multiple foes against as many targets as possible in a single big attack.

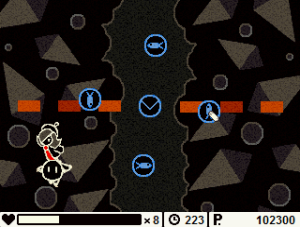

Two other colors exist, but they primarily exist to make the green obstacles and yellow enemies more difficult to deal with. Endless lines of white circles pour in at various angles to form barriers and they can be deflected away by chalk lines; white circles become completely harmless the moment they are first deflected, but a small bonus is awarded for each circle which is deflected more than once. Finally, blue objects, usually in the form of small diamonds, are not harmful on their own, but they will cancel out a chalk line if they touch it while it is still being drawn. Even though chalk cannot affect blue objects, they can be grabbed, dragged around, and flung; flinging a blue diamond at another blue diamond causes them to explode, which in turn can cause other nearby diamonds to explode in a point-granting chain reaction.

Despite the many different types of hazards to keep track of, Chalk is not at all a challenging game to complete. Line can take a surprisingly large amount of damage before losing a life. There also does not seem to be any point penalty tied to losing a life nor is any progress lost when such an event occurs. Extra lives are not particularly difficult to earn either, though even if a player does actually run out of lives they can always choose to restart from the checkpoint which is reached after defeated the midboss in each of Chalk’s six stages.

Chalk may be easy to finish, but getting high grades is another matter entirely. Precision and speed are needed for maximizing points, but time is what determines the letter-based rank you receive at the end of each stage and these skills are even more vital when aiming for an A (let alone an S). Unlike in most shmups, where enemies pour onto the screen at fixed points in time, sets of enemies and obstacles in Chalk appear after the current set is dealt with. Using enemy attacks to efficiently eliminate every threat with a single line can significantly reduce completion time while poor planning or accuracy can lead to wasting valuable seconds waiting for the enemy to leave the screen or to launch another attack. Bosses in particular can greatly affect stage completion times as they often can only be hit during brief windows of opportunity. Though I think the time-based ranking system fits well with the drawing mechanics, it is unclear as to if points factor into stage rankings at all or if they only matter for the total hi-score; players can gain the ability to start from any stage, but the rankings list only keeps track of the final total score obtained from a full run as well as the best times and grades achieved for each stage.

The real drawing point of Chalk (I had to get in at least one pun somewhere) is in its creativity. This creativity obviously extends to its aesthetics with a world of doodles defined by colorful, jagged outlines and Konjak’s signature upbeat and energetic music, but it really shines through in the ways in which the color-coded interactions are used. Yes, blue boxes can be grabbed and flung around, but you can also push down a blue lever to reset enclosing spike walls, slam blue connectors into sockets while deflecting interfering streams of white circles, and, in my favorite fight, adjust the blue hands of a clock to correctly match a time. Meanwhile, green dots are tied to rigid obstacles, but the sizes, quantities, and movement patterns of these objects when they appear constantly vary and the presence of warning arrows allows even large and fast obstacles to appear at odd angles or from multiple directions simultaneously without unfairly blindsiding the player. Every stage introduces a new color to juggle or a new twist on an old mechanic, such as the white circles which first move in slow, predictable lines in the third stage falling like meteors which must be shielded against while fighting off attackers in the fifth stage.

Bosses in particular force players to apply what they know about color interactions in new ways, such as in the case of a jet which starts out blue and must be hit with a diamond to make it flip over to its yellow side, at which point it needs to be hit by a purple attack from other nearby enemies to damage it before it leaves the screen and flips back over. The only point at which Chalk feels like it falls somewhat short is in the final stage which, other than the final boss itself, consists entirely of a boss rush against more aggressive (though less durable) versions of the previous five bosses. I often love a good boss rush, but in a game which relies so heavily on presenting players with creative surprises it feels oddly anticlimactic; a full stage or new twists on how to defeat these old nemeses would have been much more interesting than refighting identical, if slightly faster version, especially when one of those refights is against the boss from right at the end of the previous stage.

Chalk is not my favorite shmup, it’s not even my favorite game made by Konjak (that particular award goes to Noitu Love 2), but it is still a highly creative, incredibly charming, and all-around solid entry to the genre. Furthermore, though I compared Chalk to Kirby: Canvas Curse earlier with the basic concept of its drawing mechanic, it doesn’t fall all that far off the mark from the formula which makes so many of Kirby’s games in general appealing; Chalk is easy enough and forgiving enough that just about anyone can finish it without much difficulty, but it would take quite a bit of skill, and likely a good amount of persistence too, in order to ‘perfect’ the game by attaining an S rank for each stage. This is a game which took risks to present players with a uniquely charming experience and, not only did it pass the test, but it did so with flying colors.