Game Jolt Page || itch.io Page

From the creator of Tantibus comes The Gears Don’t Grind. Like most games by Benal, this puzzle platformer is short, surreal, and creative. There’s no plot to speak of and the title doesn’t make much sense other than the abstract playable character vaguely resembling a windup key, but this is also not the type of game which needs to make any sense beyond its mechanics. With 25 single-screen stages to its name, this game manages to pack in a bunch of variety over the course of less than an hour and will give you a new perspective on screen wrapping.

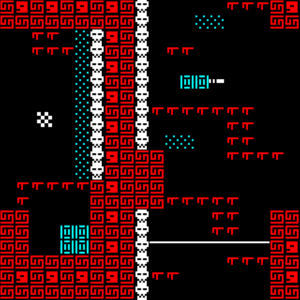

The Gears Don’t Grind is a great example of just how much can be done with a single tweak to a familiar formula. Everything seems ordinary and intuitive at a glance. You need to run and jump your way to the goal, often pushing blocks onto switches or finding keys to make other blocks disappear along the way. Touching a skull will kill the protagonist and other hazards exist along the way in the form of moving swords and switches which will cause statues to spit out deadly arrows. You can also wrap back around to the opposite side of the screen by moving beyond the border, but there is where the twist comes in. When you wrap back around your character’s relative orientation completely changes. Go through a tunnel on the right and you’ll appear back on the left, but ‘down’ will now be ‘right’ and you will fall to the right until you make contact with the left side of a wall to stand on.

The change in relative direction applies for any given direction and not just for the protagonist. You almost never need to only change directions a single time and usually must plan out a series of changes. For example, you may need to move off the screen to the right to wrap around onto a part of the ceiling leading to a hole at the top of the screen which will take you to a key which will unlock a part of the screen which can only be reaches while left is considered down. Figuring out how to reach an area which will give you the orientation you need to progress is only a piece of the puzzle and determining how to reverse these changes is yet another. Many later stages require you to spring and then dodge arrow traps or avoid strings of swords spinning at different speeds, sometimes while under time pressure, and learning to adjust quickly to which direction is which in each orientation becomes just as important as precision and planning.

The change in relative direction applies for any given direction and not just for the protagonist. You almost never need to only change directions a single time and usually must plan out a series of changes. For example, you may need to move off the screen to the right to wrap around onto a part of the ceiling leading to a hole at the top of the screen which will take you to a key which will unlock a part of the screen which can only be reaches while left is considered down. Figuring out how to reach an area which will give you the orientation you need to progress is only a piece of the puzzle and determining how to reverse these changes is yet another. Many later stages require you to spring and then dodge arrow traps or avoid strings of swords spinning at different speeds, sometimes while under time pressure, and learning to adjust quickly to which direction is which in each orientation becomes just as important as precision and planning.

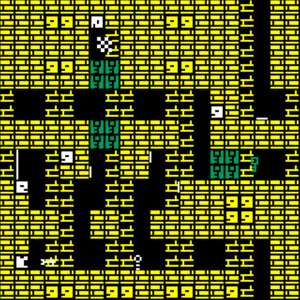

Other than your protagonist, moveable blocks can also change relative orientation once they are pushed off the screen and you will become very familiar with their rules as the game progresses. The most fundamental rule is that blocks can only be pushed while their orientation is identical to your own. You can’t push a block while standing on its side and jumping up in an attempt to push a block on the ceiling with the closest thing the protagonist has to a head won’t accomplish anything. Blocks can’t be picked up, but they can be stacked on top of each other and they become too heavy to move once stacked. Like the blocks themselves, switches can only be pressed by blocks sharing their orientation, a block on the ground will not affect a switch on the side of a wall, and blocks can no longer be moved once they are placed on a switch. Switches either remove yellow blocks or turn floating white squares into new push blocks (which always start oriented downward) and, to add a bit more complexity to puzzle solutions, the amount of switches pressed matters instead of individual switches. For instance, if you have yellow blocks in front of the exit, a block spawner, and two switches, it does not matter which of these two switches you place a block on first as, regardless of the order, the first one pressed will always turn the block spawner into a block and the second one will remove the yellow blocks in front of the exit. Since blocks can’t be moved once placed on a switch, figuring out the right order is particularly important as a block placed on a switch too early can become an insurmountable wall for a future block. The combination of the orientation mechanics mixed with new blocks often being added to the puzzle as it progresses serves as a fresh coat of paint on pushblock puzzles and allows for some very creative and complex puzzles.

Other than your protagonist, moveable blocks can also change relative orientation once they are pushed off the screen and you will become very familiar with their rules as the game progresses. The most fundamental rule is that blocks can only be pushed while their orientation is identical to your own. You can’t push a block while standing on its side and jumping up in an attempt to push a block on the ceiling with the closest thing the protagonist has to a head won’t accomplish anything. Blocks can’t be picked up, but they can be stacked on top of each other and they become too heavy to move once stacked. Like the blocks themselves, switches can only be pressed by blocks sharing their orientation, a block on the ground will not affect a switch on the side of a wall, and blocks can no longer be moved once they are placed on a switch. Switches either remove yellow blocks or turn floating white squares into new push blocks (which always start oriented downward) and, to add a bit more complexity to puzzle solutions, the amount of switches pressed matters instead of individual switches. For instance, if you have yellow blocks in front of the exit, a block spawner, and two switches, it does not matter which of these two switches you place a block on first as, regardless of the order, the first one pressed will always turn the block spawner into a block and the second one will remove the yellow blocks in front of the exit. Since blocks can’t be moved once placed on a switch, figuring out the right order is particularly important as a block placed on a switch too early can become an insurmountable wall for a future block. The combination of the orientation mechanics mixed with new blocks often being added to the puzzle as it progresses serves as a fresh coat of paint on pushblock puzzles and allows for some very creative and complex puzzles.

There are two issues of note in The Gears Don’t Grind and, as the nature of block puzzles touches on both of them, it’s best to address them now. Minimalism works in this game’s favor with its simplistic yet pleasing aesthetic, but it causes two faults on the gameplay side of things. The more minor of these issues is the apparent lack of a retry button. Just about every stage has at least one skull in it for you to toss the protagonist at if a puzzle becomes unsolvable, but navigating to this skull after realizing you’ve made a mistake can sometimes be a challenge in and of itself. Alternately, you can return to the title screen and choose to restart the level from there, but this is still a significantly more time-consuming process than pressing a dedicated button. The second issue is one of indication in relation to block spawns. Many levels have multiple block-generating squares, but the lack of indication as to the order in which switches will turn squares into blocks can make it difficult to tell where each block is meant to go on a first try. This isn’t generally an issue, but there were two levels in which I had to restart because of the blocks appearing in a different order than what I had assumed.

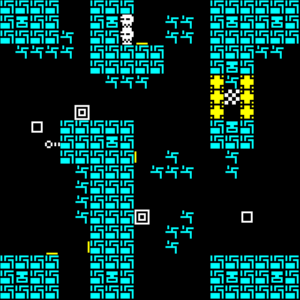

Though this game may be small, it has more to offer than blocks and hazards. White lines serve as trampolines which grant additional jump height when approached from the proper side at the cost of effectively serving as one-way doors. Warp points can be approached from above and below and take you to different warps depending on which direction they are entered from. Warps aren’t used frequently, but each warp serving as a door to two different points makes figuring out how they are all connected a bit more complicated than usual. Sets of blue platforms also exist which become solid or insubstantial every time you jump. I particularly like these blue platforms because they are usually used in two alternating sets to force you to limit your jumping and think carefully about just where you want to go when and what you can reach through falling without jumping. In one stage these platforms are even used as a jump counter; jump too many times and a block will fall on a switch which removes a set of yellow blocks needs in order to reach the exit. There’s even a final boss fight, though it largely boils down to memorizing where the boss appears while pushing blocks on switches and avoiding swords.

Though this game may be small, it has more to offer than blocks and hazards. White lines serve as trampolines which grant additional jump height when approached from the proper side at the cost of effectively serving as one-way doors. Warp points can be approached from above and below and take you to different warps depending on which direction they are entered from. Warps aren’t used frequently, but each warp serving as a door to two different points makes figuring out how they are all connected a bit more complicated than usual. Sets of blue platforms also exist which become solid or insubstantial every time you jump. I particularly like these blue platforms because they are usually used in two alternating sets to force you to limit your jumping and think carefully about just where you want to go when and what you can reach through falling without jumping. In one stage these platforms are even used as a jump counter; jump too many times and a block will fall on a switch which removes a set of yellow blocks needs in order to reach the exit. There’s even a final boss fight, though it largely boils down to memorizing where the boss appears while pushing blocks on switches and avoiding swords.

There isn’t much here that you probably haven’t seen before in another game other than the way changing orientation works, but that’s entirely fine. With this single unique trait and a handful of minor tweaks, The Gears Don’t Grind manages to turn old mechanics on their heads with the result being an experience which is at once intuitive and innovative.